De Mysteriis

Published:

August 4, 2025

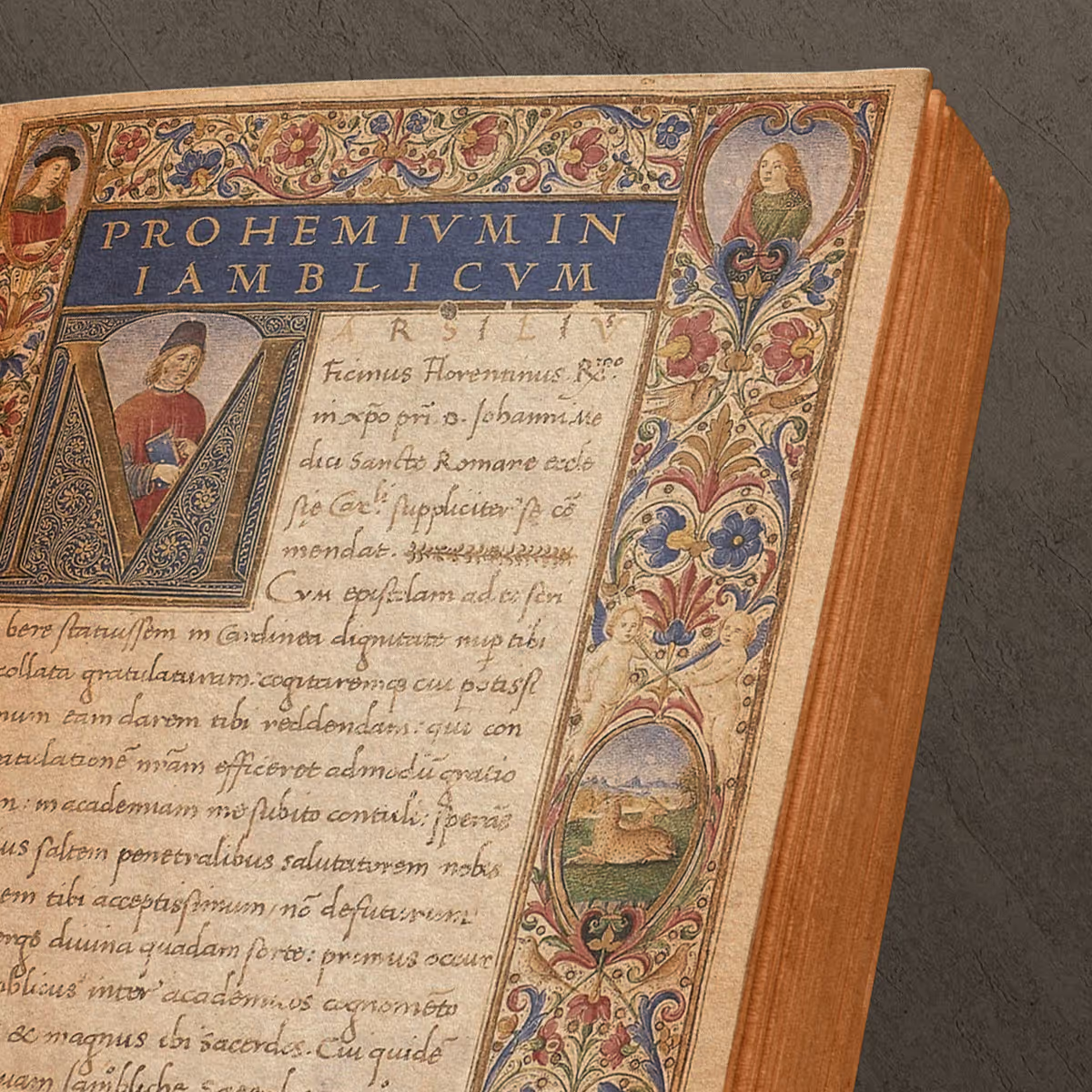

Ficino’s Hermetic Vision

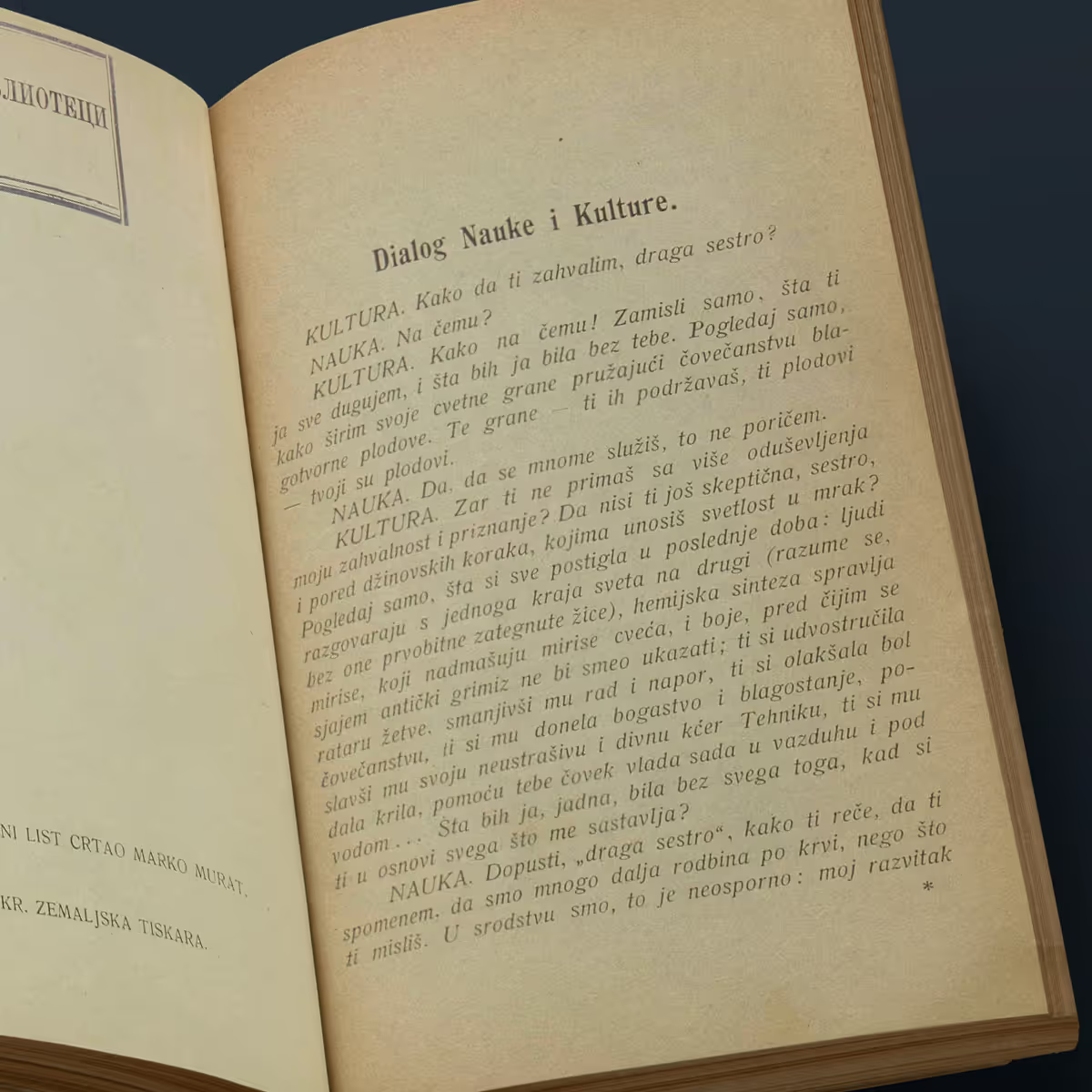

Marsilio Ficino’s Latin translation of Iamblichus’ De Mysteriis stands as a pivotal intersection of Renaissance humanism and Hermetic philosophy. Iamblichus, the Neoplatonist philosopher, crafted a visionary text exploring divine, celestial, and earthly hierarchies, theurgy, and the soul’s ascent. Ficino’s translation was more than linguistic; it brought this esoteric knowledge into fifteenth-century Europe, allowing scholars and practitioners to engage with metaphysical speculation alongside the revival of Platonic thought. By preserving Iamblichus’ spiritual and theurgical insights, Ficino ensured that De Mysteriis became a touchstone for Renaissance thinkers seeking to reconcile occult wisdom with humanist ideals, illuminating the interplay of intellect, soul, and cosmos and guiding both contemplation and the pursuit of knowledge.

Legacy in the Renaissance

Ficino’s work ensured Iamblichus’ Hermetic vision influenced not only occult philosophy but the broader currents of European thought, shaping the ways scholars approached metaphysics, magic, and the pursuit of spiritual knowledge.

“The sacred symbols are not empty signs, but vessels filled with divine presence. Through them the gods shine forth, awakening their hidden light already dwelling within the soul.”

Translated excerpt from De Mysteriis on symbols

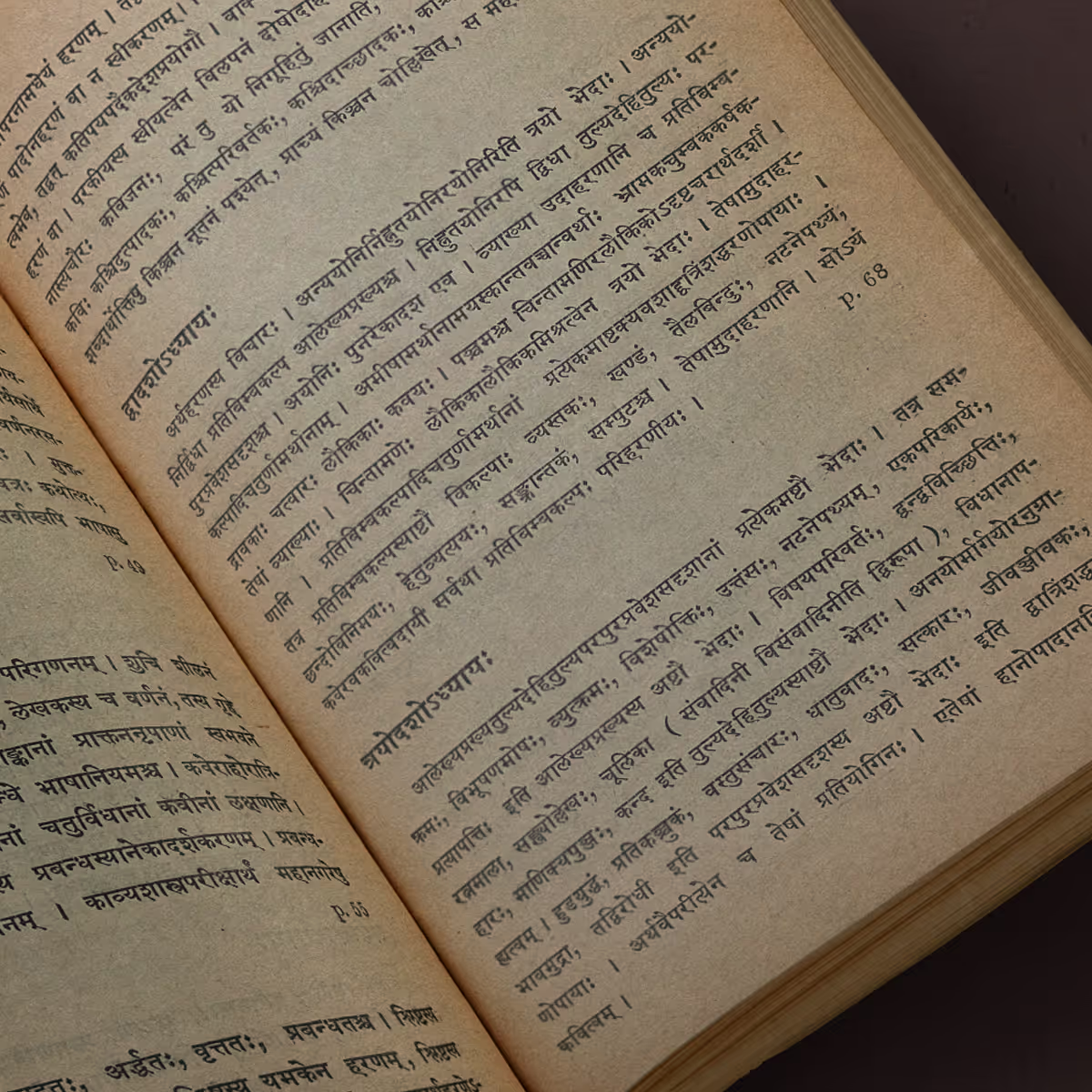

The “symbols” (σύμβολα, sýmbola)

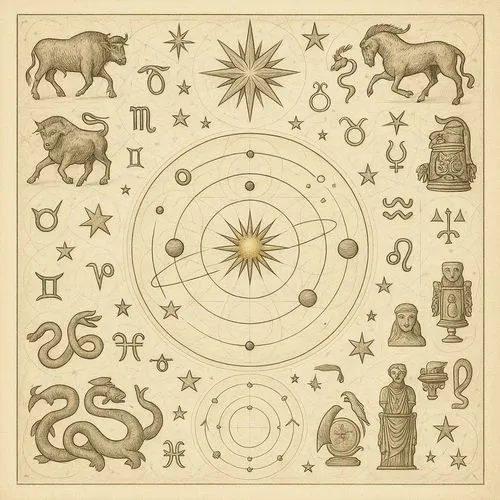

In De Mysteriis (On the Mysteries), Iamblichus defends theurgy—the ritual practices meant to connect the human soul with the divine. The “symbols” (σύμβολα, sýmbola) he refers to are not just decorative signs, but sacred tokens believed to carry real divine power. Here’s a breakdown:

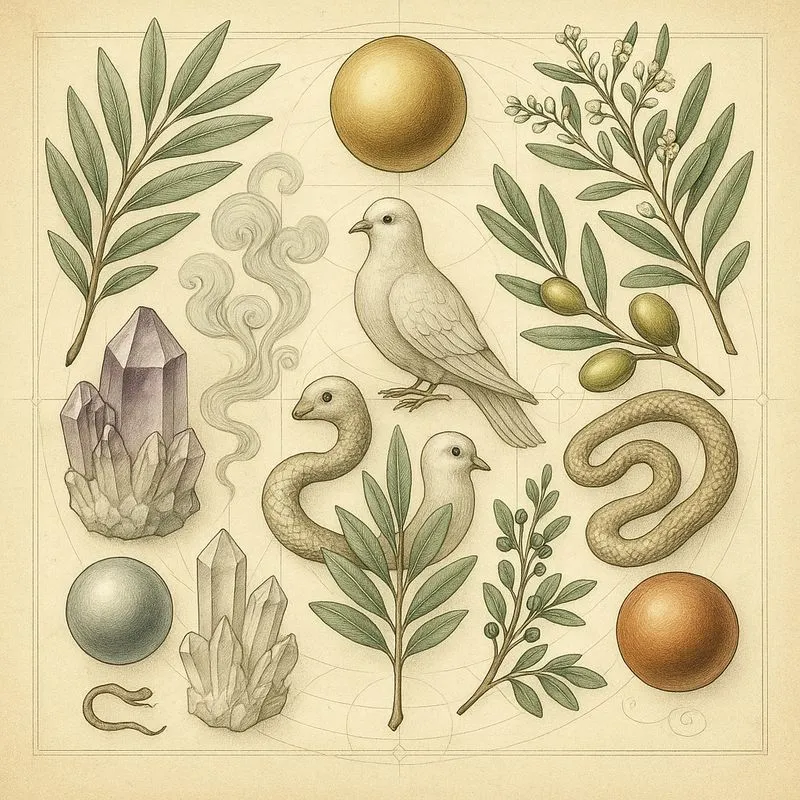

Material Symbols

Iamblichus stresses that physical objects used in ritual—stones, plants, animals, metals, incense—are not arbitrary, but natural “signatures” of divine forces. They are thought to embody the energies of gods or daimones, allowing humans to access divine presence through them.

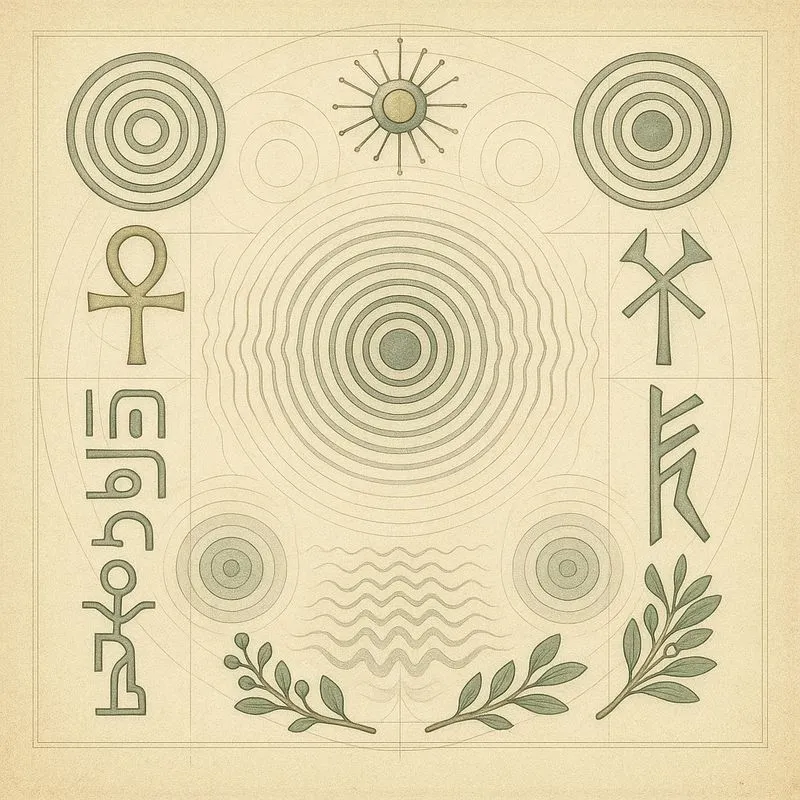

Sacred Words and Chants

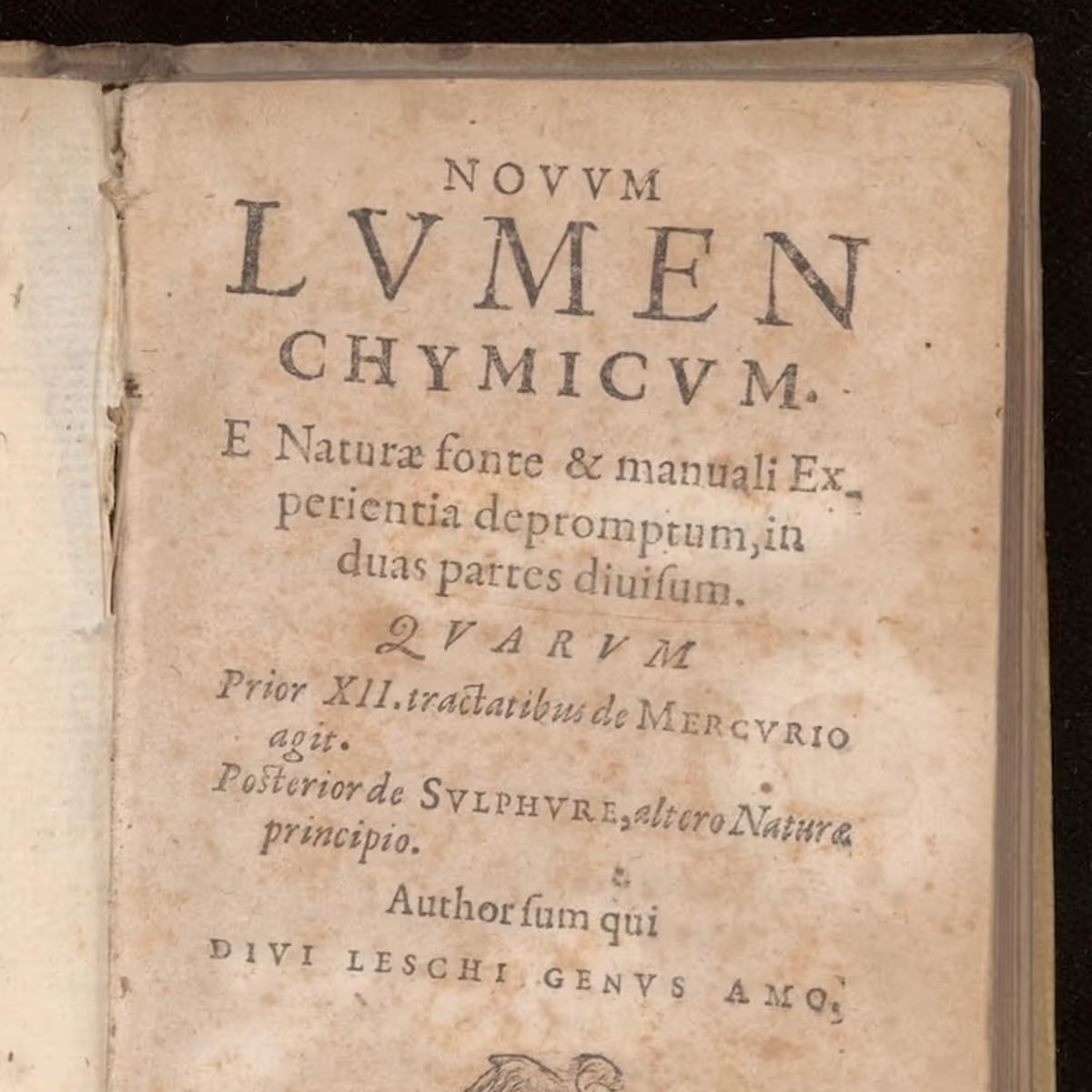

Vocal formulas, divine names, and “barbarous” words of power (often Egyptian or Chaldean in origin) function as symbols. The language itself was considered non-discursive—its sound and vibration carried a sacred efficacy beyond rational meaning.

Numbers and Geometric Forms

Pythagorean number-symbolism and Platonic geometry are deeply embedded in Neoplatonism. Numbers (like the Monad, Dyad, Triad) and shapes (circle, triangle, square) were treated as divine symbols expressing the structure of the cosmos.

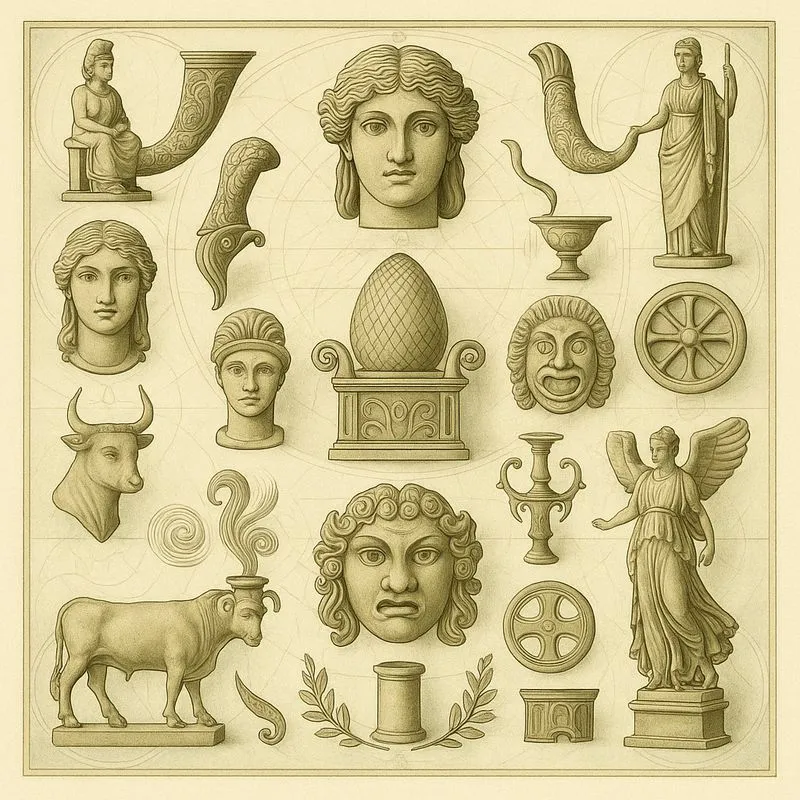

Mythic Images and Statues

Cult statues and images (agalma) weren’t just representations but embodiments of divine presence. Iamblichus defends their use as conduits for the gods, provided rituals are performed correctly. They functioned as symbolic “anchors” for divine descent.

Ritual Gestures and Actions

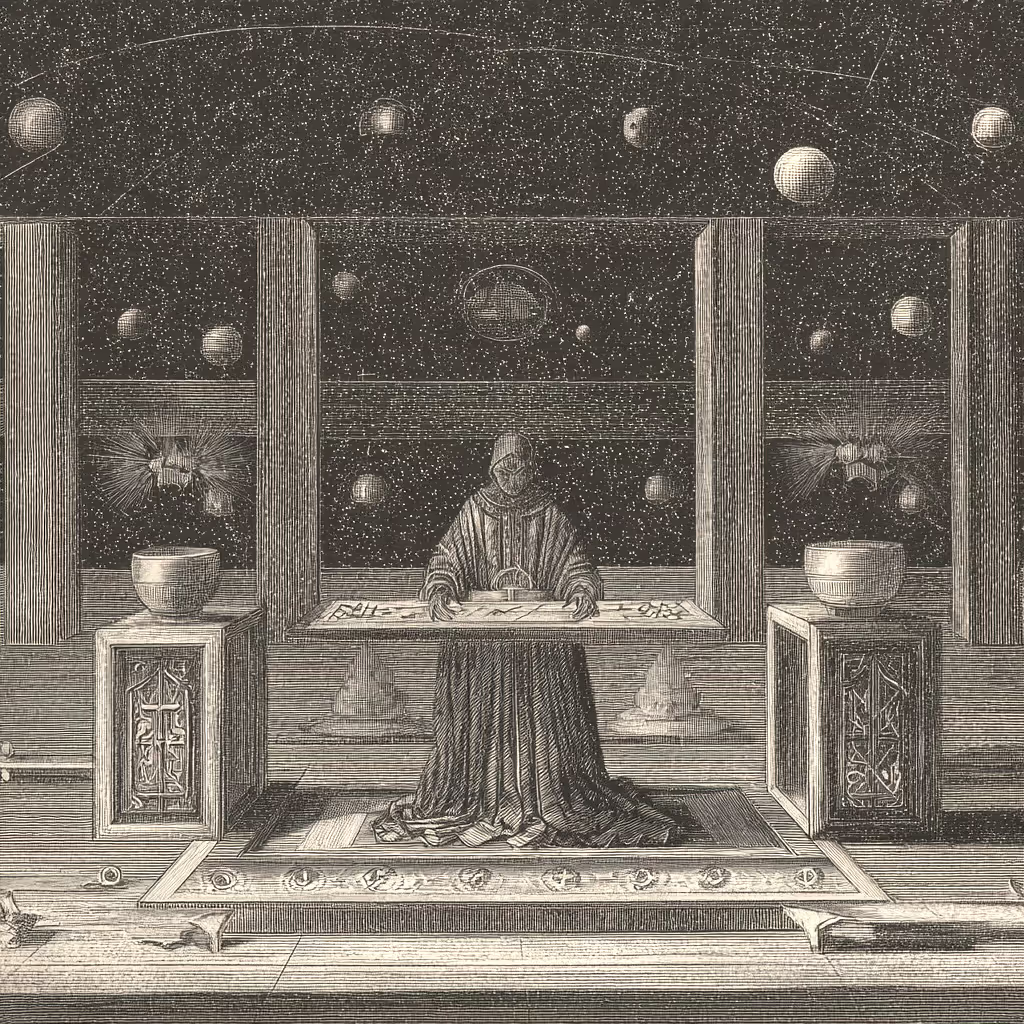

Movements, purifications, offerings, and even silence were themselves considered symbols—acts that mirror higher cosmic processes. By performing them, the theurgist “aligned” human activity with divine order.

Cosmic Symbols

The stars and planets themselves were regarded as divine symbols. Astrology, for Iamblichus, wasn’t just predictive but a symbolic map of divine intelligences and their operations. Ritual timing according to stellar positions was a way to “read” and “activate” these symbols.

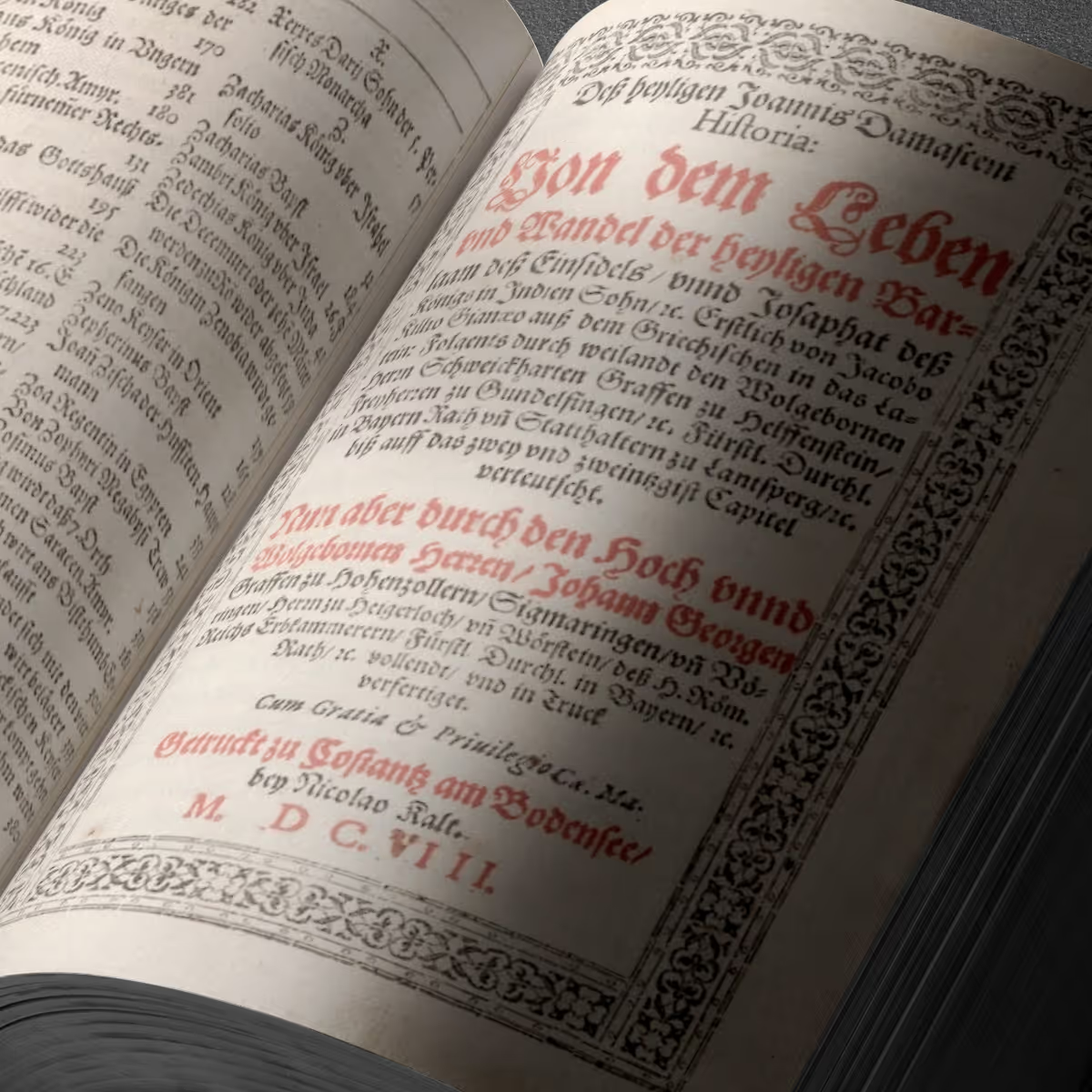

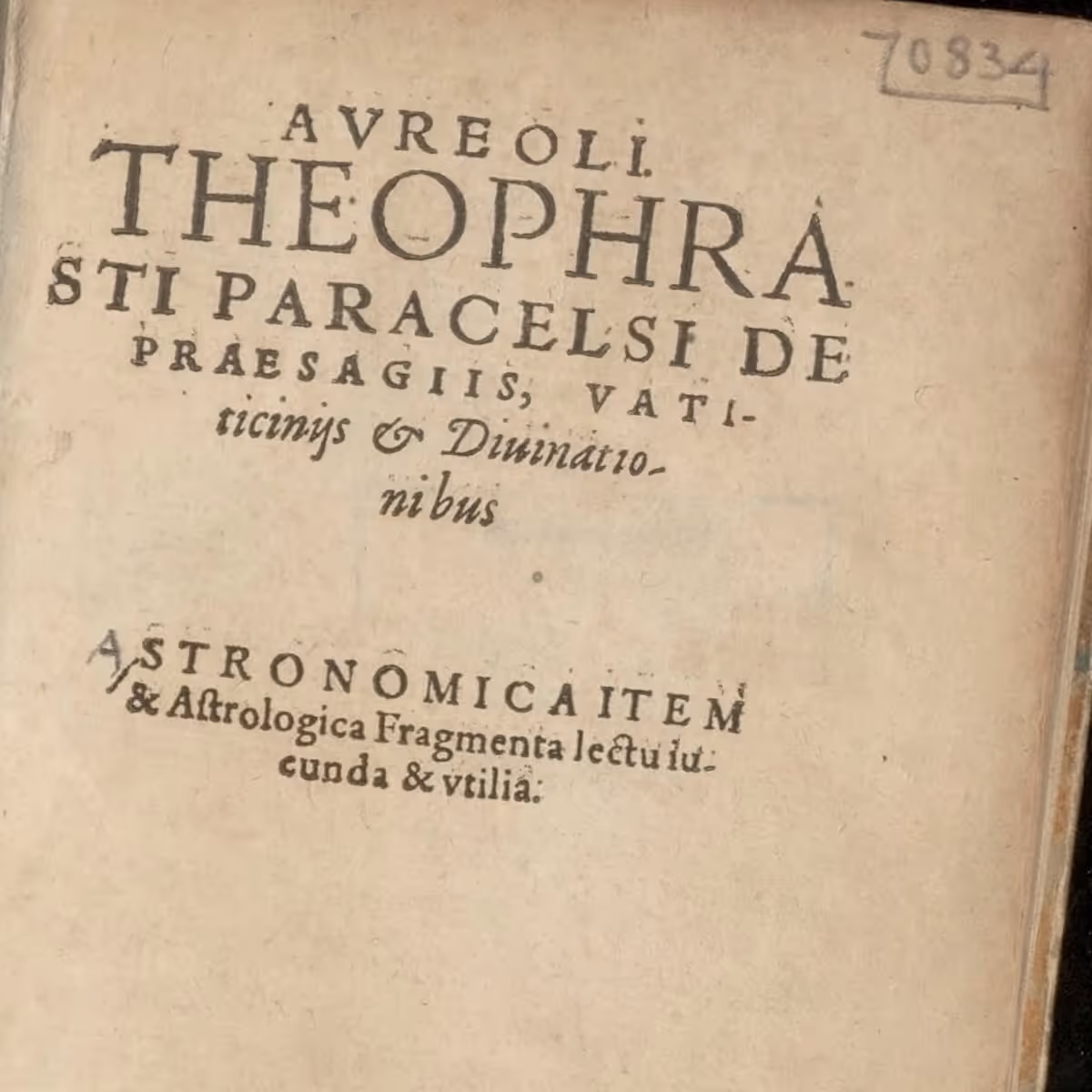

Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499)

Marsilio Ficino was a pivotal figure in the Italian Renaissance, renowned as a philosopher, scholar, and priest. He played a key role in reviving Neoplatonism, blending classical philosophy with Christian theology. As the head of the Platonic Academy in Florence, sponsored by the Medici family, Ficino translated and commented on Plato’s works and other ancient texts, making them accessible to the Western world. His influential writings, including Theologia Platonica, explored the immortality of the soul and the harmony between philosophy and religion. Ficino’s ideas profoundly shaped Renaissance humanism, art, and intellectual thought, leaving a lasting legacy in Western philosophy.

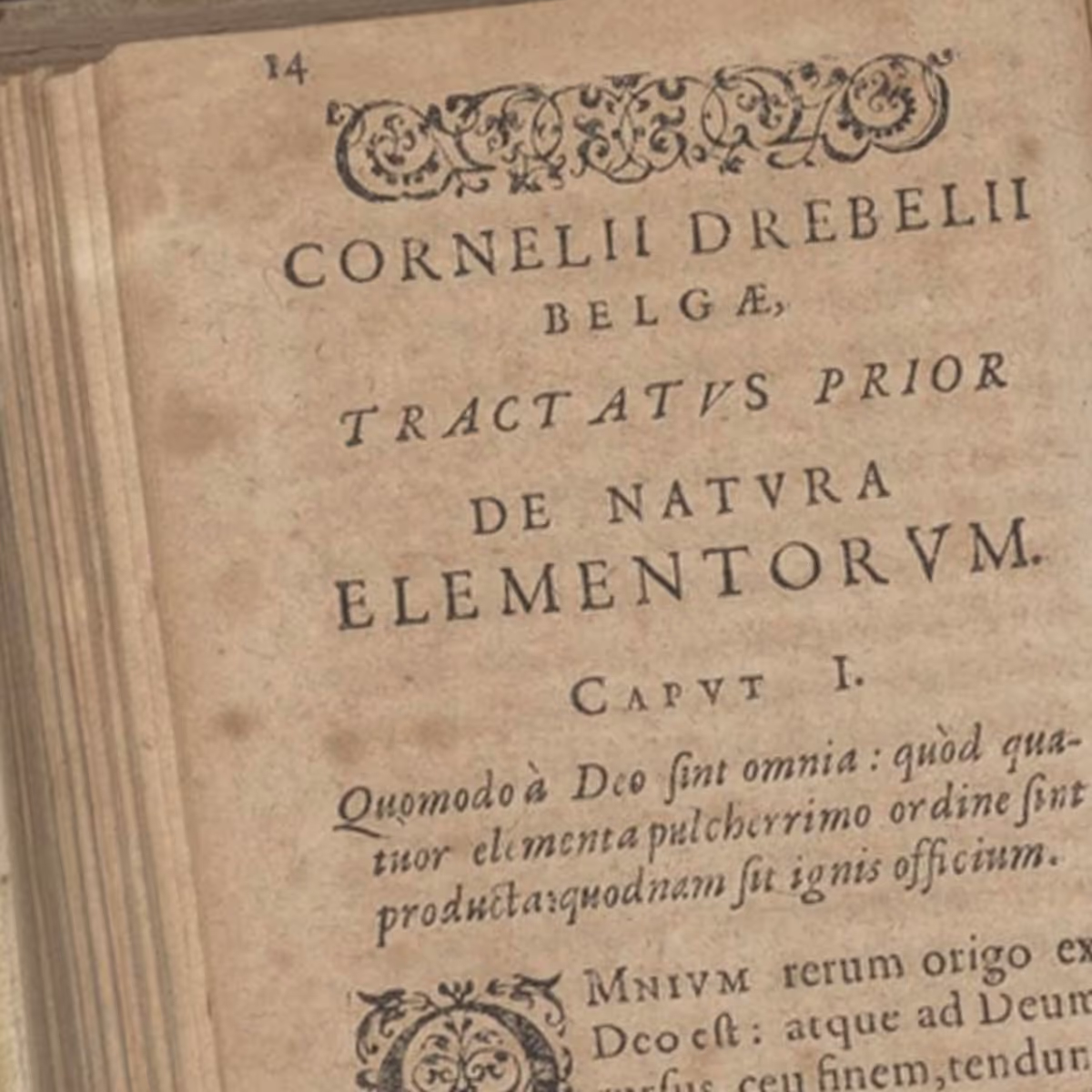

Iamblichus (c. 245–325 CE)

Iamblichus was a Syrian philosopher and a key figure in Neoplatonism, a philosophical school founded by Plotinus. A student of Porphyry, Iamblichus expanded Neoplatonic thought by emphasizing theurgy, the practice of rituals to connect with divine beings and achieve spiritual ascent. His influential works, such as On the Mysteries of the Egyptians, explored metaphysics, theology, and the role of divine intervention in human life. Iamblichus’ teachings bridged philosophy and religion, profoundly shaping later Neoplatonic thought and influencing medieval and Renaissance philosophy.