Adam Smith's “invisible hand” is one of the most famous metaphors in intellectual history. But the idea that markets self-organize into beneficial order — that individual actions, guided by no central plan, can produce collective harmony — did not spring fully formed from the Wealth of Nations in 1776. It has a lineage stretching back through Reformation theologians, Renaissance merchants, Scholastic monks, and ancient philosophers. Source Library has assembled the primary sources that make this lineage readable for the first time in a single collection.

The Ancient Problem: How Can Exchange Be Just?

The story begins with a puzzle in Book V of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics (our copy: a 1521 edition with Averroes's commentary). How can a house and a pair of shoes be equated in exchange? They are utterly different things. Aristotle's answer — that money serves as a measure of need or demand — launched two thousand years of debate about whether value is intrinsic to objects or arises from the desires of those who want them.

In the Politics (1515 edition), Aristotle drew a sharper distinction. Natural acquisition — producing food, raising livestock — has a natural limit. But chrematistics, the art of money-making through trade, appears to have no natural boundary. “Of the art of acquisition there is one kind which by nature is a part of the management of a household… and there is a second kind which is generally called the art of wealth-getting.” Money is “barren,” Aristotle declared — it cannot beget money. This became the intellectual foundation for the medieval prohibition on usury and framed economic thinking for the next two millennia.

Xenophon's Oeconomicus (1539 Latin edition) gave the discipline its name. “Economics” is literally oikonomikos — household management. A Socratic dialogue about running an estate, it already contains insights about the division of labour, the value of organisation, and why specialisation makes everyone richer. Smith would make the same argument about a pin factory twenty-two centuries later.

The Scholastic Revolution: Markets as Moral Order

For centuries, Aristotle's authority on economic questions was mediated through one text above all: the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas. Questions 57–79 of the Secunda Secundae treat justice; Question 77 addresses the just price in buying and selling; Question 78 covers usury. Aquinas's crucial insight — underappreciated for centuries — was that the just price is simply the common market price. Not a price calculated by philosophers or decreed by kings, but the price that emerges from the ordinary transactions of buyers and sellers. Already, buried in 13th-century Latin, is a form of market theory.

Nicole Oresme pushed further. His Traictie de la Premiere Invention des Monnoies (c. 1355) is the earliest systematic monetary treatise in Western thought. Writing during the chaos of medieval currency debasement, Oresme argued that money belongs to the community, not the prince, and that manipulating the currency is a form of theft. His analysis of how debased coinage drives good money out of circulation anticipated Gresham's Law by two hundred years.

“The community, who use the coin, are the true owners thereof; and the prince has no right to alter money to the detriment of his subjects.”

— Nicole Oresme, De Moneta, c. 1355

The Florentine Laboratory

Before anyone wrote the theory, Florence lived it. Between the 13th and 16th centuries, the city on the Arno became the most commercially sophisticated place in Europe — and produced a body of practical economic writing that has no equivalent in the medieval world.

Francesco Balducci Pegolotti was a factor for the Bardi banking house — one of the great Florentine firms that financed Edward III's wars and went spectacularly bankrupt when he defaulted. His Pratica della Mercatura (c. 1340) is an astonishing trade handbook covering exchange rates, commodity weights, tariffs, and trade routes from London to Beijing. It records commercial practice as it actually was, not as theologians thought it should be.

Poggio Bracciolini (De Avaritia, 1428) wrote a humanist dialogue on greed that was remarkably sympathetic to merchants. Where the Scholastics agonised over whether trade was sinful, Bracciolini's characters argue that the desire for wealth drives civilisation forward. A Florentine anticipation of Mandeville by three centuries.

Leon Battista Alberti (I Libri della Famiglia, c. 1434) codified the Florentine merchant ethic into a treatise on household economy. Book III, on masserizia (thrift, prudent management), describes the ideal that every Florentine banker aspired to — rational allocation of resources, avoidance of waste, the virtuous accumulation of wealth through industry. This is the domestic counterpart to the commercial world Pegolotti documented.

Benedetto Cotrugli (Della Mercatura et del Mercante Perfetto, written c. 1458, published 1573) produced the earliest known description of double-entry bookkeeping — predating Luca Pacioli 's famous Summa de Arithmetica (1494) by thirty-five years. Pacioli systematised the method, but Cotrugli's four books on mercantile life — covering trade, the merchant's character, accounting, and maritime commerce — give us the fullest portrait of the commercial mind that made the Renaissance possible.

Machiavelli (Istorie Fiorentine, 1525) wrote the history of all this from the inside — the Medici banking empire, the factional economics of the guilds, the relationship between commercial wealth and political power. Luca Landucci (Diario Fiorentino, 1450–1516) recorded it from below: an apothecary's diary tracking commodity prices, economic conditions, and daily commercial life in Medici-era Florence.

The Calimala guild statutes (1301) show the institutional infrastructure: the rules governing the cloth importers' guild that was Florence's economic engine. And Pagnini (Della Decima, 1765) compiled the fiscal records — taxation, currency, and the trade agreements by which Florence projected its commercial power. This is where Pegolotti's Pratica was first published, three and a half centuries after it was written.

The School of Salamanca: The Actual Inventors of Economics

The most important chapter of this story is the least known. In the 16th century, a group of Dominican and Jesuit theologians at the University of Salamanca — grappling with the flood of New World silver and the explosion of Atlantic commerce — effectively invented modern economic analysis. They did so two centuries before Adam Smith, and they did it in Latin treatises on justice and natural law that have never been widely read outside specialist circles.

Francisco de Vitoria (1557 edition of the Relectiones Theologicae) founded the school. His lectures on justice, international trade, and the rights of indigenous peoples established the framework that his students built upon. Vitoria argued that trade is a natural right — not merely a privilege granted by sovereigns — and that just war cannot be waged to create trade monopolies.

Domingo de Soto (De Iustitia et Iure, 1553) bridged medieval Thomism and the new commercial reality. His ten books on justice treated exchange, usury, and the morality of commerce with a rigour that directly influenced the next generation.

Martín de Azpilcueta (Comentario Resolutorio de Usuras, 1568) formulated the quantity theory of money decades before Jean Bodin usually gets the credit. Watching Spanish prices soar as American silver flooded the markets, Azpilcueta reasoned that money, like any commodity, is worth less where it is abundant. A simple observation with enormous consequences.

Tomás de Mercado (Summa de Tratos y Contratos, 1571) wrote a practical manual for merchants navigating the new Atlantic economy — covering just price, foreign exchange, insurance, and usury. Written in Spanish rather than Latin, it was meant to be read by the traders themselves, not just the theologians.

Luis de Molina (De Iustitia et Iure, 1614 edition) produced the most comprehensive Salamanca treatment of economic questions. Disputations 347–406 cover price formation, money, credit, exchange, and banking with an analytical sophistication that would not be matched for generations. Molina argued explicitly that the just price is determined by supply and demand — by the “common estimation” of the market — not by the cost of production.

Leonardus Lessius (De Iustitia et Iure, 1608), a Jesuit at Louvain, wrote what the economic historian Raymond de Roover called “the most exhaustive treatment of business ethics written during the period.” Book II covers property, contracts, money, exchange, banking, insurance, and interest. Lessius synthesised the entire Salamanca tradition into its most refined form.

Italian Merchants and the Theory of Money

While the Salamanca theologians reasoned from Aristotle and Scripture, Italian merchant-scholars approached the same problems from commercial practice. Gasparo Scaruffi (L'Alitinonfo, 1582 — a Greek coinage meaning “true light”) proposed a universal monetary standard based on fixed gold-silver ratios, a rationalist vision of monetary order. Bernardo Davanzati (Lezione delle Monete, 1588) argued that money has no intrinsic value whatsoever — its worth derives purely from social convention and utility. This proto-subjectivist theory of value would take three centuries to be rediscovered by the Austrian School.

Sigismondo Scaccia (Tractatus de Commerciis et Cambio, 1650) bridged the theological and commercial traditions, producing a major treatise on commercial law covering exchange, usury, deposits, and bills of exchange.

Natural Law and the Right to Trade

The Salamanca insight — that market prices reflect a natural order of human desires — needed a new philosophical framework. The natural law tradition provided it. Hugo Grotius (De Iure Belli ac Pacis, 1631) grounded property rights and commercial obligations in natural law rather than divine revelation, making economic reasoning accessible to secular philosophy. Samuel von Pufendorf (De Officio Hominis et Civis, 1673) distilled these arguments into the textbook that taught two centuries of European university students about natural duties including economic conduct.

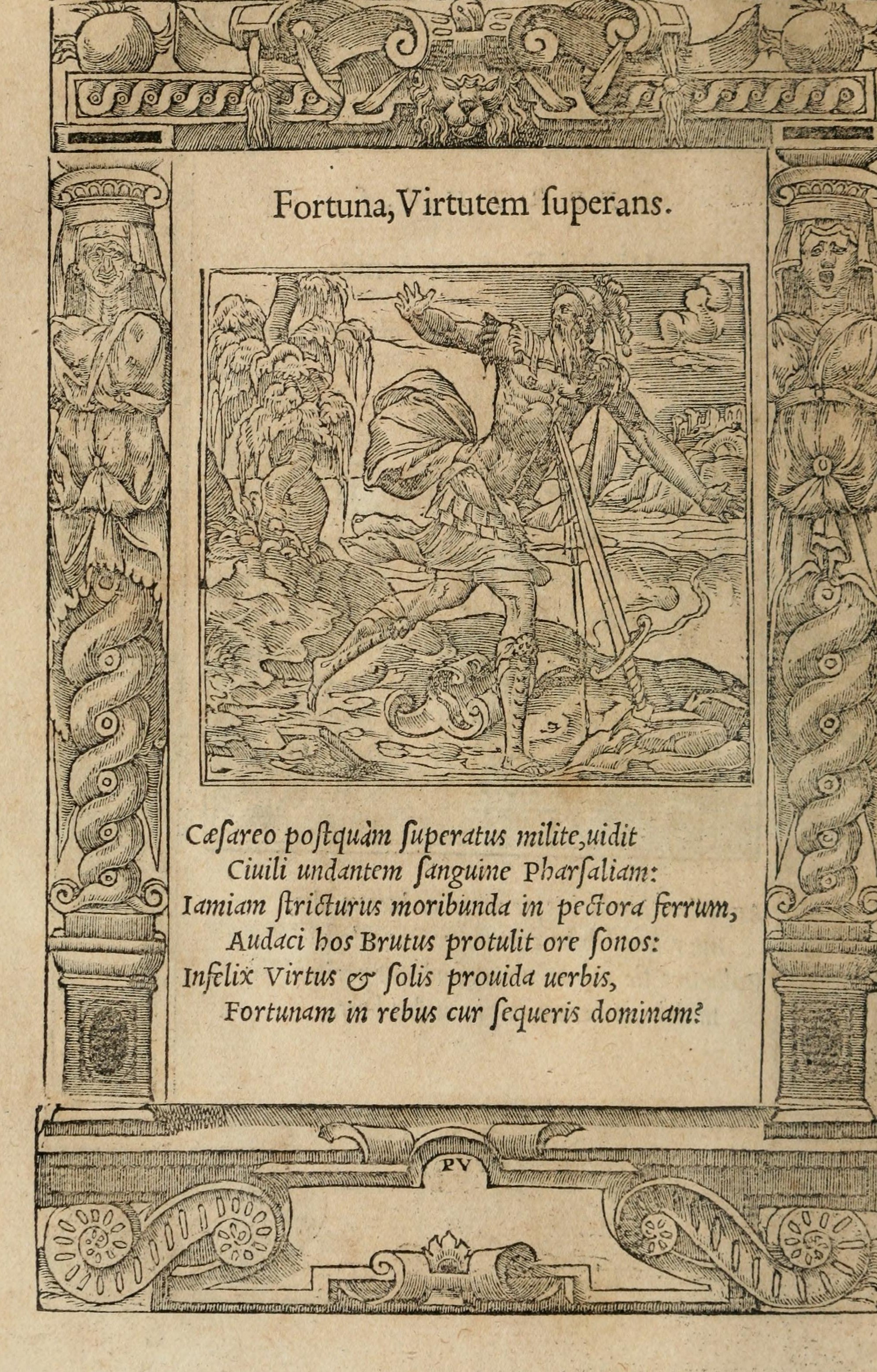

Juan de Mariana (De Rege et Regis Institutione, 1605) pushed the political implications further than anyone before. A Jesuit who had already argued that tyrannicide could be justified, Mariana insisted that the king has no right to debase the currency, tax without consent, or create monopolies. Philip III of Spain ordered the book burned.

The English 1690s: A Revolution in Economic Thought

In the 1690s, within a few years of each other, four English writers produced pamphlets that anticipated nearly everything Smith would say a century later:

Nicholas Barbon (A Discourse of Trade, 1690) stated the subjective theory of value with startling clarity: “the Value of all Wares arises from their Use.” Things have no intrinsic value; all value comes from the wants and needs of the user. This directly contradicts the labour theory of value that would mislead economists from Smith through Marx.

Sir William Petty (Political Arithmetick, 1690) founded quantitative economics. He insisted on “Number, Weight, and Measure” rather than “superlative Words, and intellectual Arguments” — the first systematic attempt to measure national income, labour productivity, and state resources empirically.

Sir Dudley North (Discourses upon Trade, 1691) produced the clearest pre-Smithian argument for free trade in just 41 pages. Trade restrictions harm national wealth; interest rates should be set by markets, not legislatures; and “the World as to Trade, is but one Nation or People.”

John Locke (Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest, 1692) argued that interest rates, like prices, are set by the supply and demand for money — not by legislative fiat. A direct application of natural law thinking to monetary policy.

The Moral Sense Pipeline: From Cambridge to Glasgow

The economic arguments needed a moral psychology to stand on. How do humans cooperate without a central coordinator? The answer came through a chain of thinkers that ran from Cambridge to Edinburgh.

Ralph Cudworth (The True Intellectual System of the Universe, 1678) argued that the cosmos is governed by rational, intelligible principles — a “plastic nature” that produces order without external micromanagement. Cudworth was the step-grandfather of the Third Earl of Shaftesbury, and his cosmic rationalism flowed directly into the next generation.

Joseph Butler (The Analogy of Religion, 1736) argued that the same providential order visible in nature extends to morality. This is the theological architecture that makes the invisible hand philosophically legible — if the natural world shows design, then the market's self-organisation can be read as evidence of the same ordering principle.

The Third Earl of Shaftesbury translated Cudworth's metaphysics into a moral aesthetics. His Characteristicks (1714, already in our collection) argued for an innate moral sense — a natural capacity to perceive right and wrong as directly as we perceive beauty. Francis Hutcheson systematised this into a full System of Moral Philosophy (1755), which he taught at Glasgow to a young student named Adam Smith.

Lord Kames (Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion, 1751) — Hume's patron, Smith's mentor — argued for a moral sense implanted by divine providence. This is the direct intellectual context for Smith's “impartial spectator.”

Adam Ferguson (An Essay on the History of Civil Society, 1767) articulated what would become the concept of spontaneous order: “Nations stumble upon establishments, which are indeed the result of human action, but not the execution of any human design.” This single sentence is the intellectual ancestor of Hayek's entire programme.

Smith and Beyond: From Invisible Hand to Economic Harmonies

By the time Smith wrote, the philosophical groundwork was extensive. His Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue and Arms (reconstructed from student notes of 1763–64) show his full system before he distilled it into the Wealth of Nations — jurisprudence, political economy, and military policy unified under natural law principles inherited from Hutcheson, Kames, and the entire tradition behind them.

Dugald Stewart (Biographical Memoirs, 1811) recorded the intellectual genealogy. His memoir of Smith — read before the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1793 — is the single most important source for understanding how Smith saw himself within this tradition.

Thomas Reid (Essays on the Active Powers of the Human Mind, 1788) and William Paley (Natural Theology, 1802) completed the philosophical framework: human agency operating within a providentially ordered universe, producing beneficial outcomes not through central planning but through the exercise of natural faculties.

Meanwhile, Bernard Mandeville (The Fable of the Bees, 1724) had scandalised polite society with the opposite argument: “Private Vices, Publick Benefits.” Selfishness and vanity, not virtue, drive economic prosperity. Where Hutcheson and Smith saw moral harmony, Mandeville saw a useful paradox. The debate between them — is economic order moral or merely functional? — remains unresolved.

The French Tradition: Harmonies All the Way Down

The idea of economic harmony found its most explicit expression in France. Pierre de Boisguilbert (Le Détail de la France, 1707) was the first to systematically argue that agricultural prosperity, not gold accumulation, is the source of national wealth — anticipating the Physiocrats. François Quesnay (Oeuvres Économiques, Oncken edition) built the Tableau Économique, the first model of the economy as a self-regulating circular flow.

Richard Cantillon (Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Général, 1755) — written in French but by an Irish-born Paris banker — is the most important economic text between the Salamanca School and Smith. Cantillon analysed how money enters the economy through specific channels, how prices adjust to new supplies of precious metal, and how entrepreneurial decision-making coordinates production. Schumpeter called it “the first systematic penetration of the field of economics.”

Turgot (Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth, 1793 English translation of the 1766 original) anticipated marginal utility theory and wrote the clearest pre-Smithian account of capital formation. Condillac (Le Commerce et le Gouvernement, published the same year as the Wealth of Nations, 1776) produced a subjective value theory arguably more sophisticated than Smith's labour theory — the proto-Austrian text. Jean-Baptiste Say (Treatise on Political Economy, 1821 English edition) reformulated Smith for a Continental audience and contributed Say's Law — “supply creates its own demand” — the most contested proposition in the history of economics.

And then Frédéric Bastiat made the metaphor explicit. His Harmonies économiques (1850) argued that the apparent conflicts between classes, between producers and consumers, between nations, are illusory — that underneath them lies a harmony of interests as real and as lawful as the harmonies of the physical world. The title is not accidental. Bastiat was consciously connecting economic theory to the tradition of cosmic harmony that runs from Pythagoras through Kepler.

What This Collection Makes Possible

The standard history of economics begins with Smith and proceeds to Ricardo, Mill, Marx, and the marginalists. This is like beginning the history of physics with Newton. The earlier tradition is not merely a prelude; in many ways it is more sophisticated. Molina's subjective price theory, Cantillon's monetary analysis, Barbon's theory of value, Oresme's monetary constitutionalism — these anticipate ideas that would be “discovered” centuries later.

Source Library now holds original editions of the complete chain — from Aristotle's Ethics through Florentine merchant manuals, Aquinas, and the Salamanca School to Smith and Bastiat. As these texts are processed through our OCR and translation pipeline, they become searchable and cross-referenceable for the first time. A researcher studying Molina's price theory can trace its debts to Aquinas, compare it with the commercial practice recorded in Pegolotti and Cotrugli, follow its parallels with Davanzati, and track its echoes in Cantillon — all within a single reading environment.

The English-language texts from the 18th century — Hutcheson, Shaftesbury, Ferguson, Kames, Butler, Mandeville, Smith's Lectures — will also pass through our modernisation pipeline, which rewrites early modern English into clear, accessible modern prose while preserving the author's arguments. These are important texts that remain difficult to read in their original form. Making them accessible does not diminish them; it lets them speak again.

The invisible hand, it turns out, has a very long history. And that history looks less like a single insight and more like a conversation — carried on across languages, centuries, and continents — about whether the order we observe in human exchange is a sign of something deeper in the structure of things.

The texts discussed in this essay are available to read and search at sourcelibrary.org. All are original historical editions digitised from Internet Archive, Gallica, and other institutional sources. OCR and translation are in progress across the collection.